Back in October 2019, we published a blog post on the challenges of building a high-performance network (HPN). We landed on the conclusion that an HPN should be designed with sensitivity to local market dynamics, provider relationships, and performance sustainability; we rejected the premise that you can build an HPN simply by “casting a net” to capture providers who are high quality and low cost.

But what about the inverse proposition? If you can’t build an effective a narrow network to filter in the best of the best, could you build a narrow-er network by filtering out the worst of the worst?

This isn’t an unprecedented idea. Notably, the 32BJ Health Fund announced in June 2021 that it would sever ties with the NewYork-Presbyterian health system for the 2022 Plan Year, citing high prices as the first factor in its decision. (It also cited barriers regarding the continuation of its High-Value Maternity Network program).

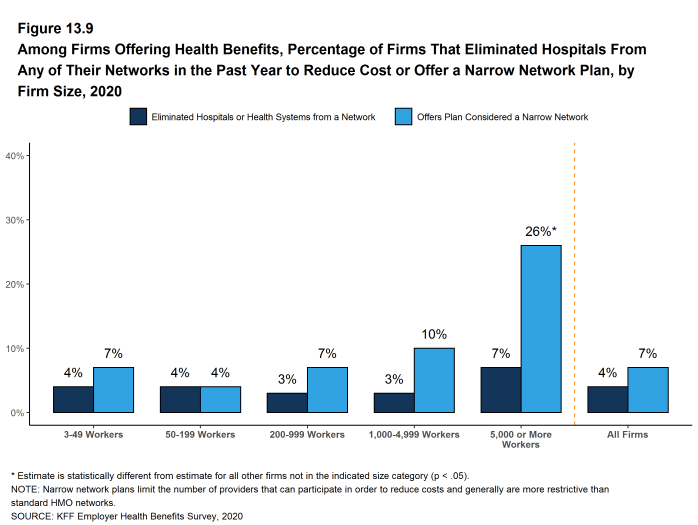

But, altogether, removing low-performing hospitals from a network hasn’t gained much traction in the marketplace. According to the 2020 Employer Health Benefits Survey from the Kaiser Family Foundation, only 4% of surveyed firms “eliminated a hospital or health system from a provider network during the past year in order to reduce the plan’s cost.” Moreover, these are hospitals and health systems that were removed to reduce costs, not to improve quality.

But just because it hasn’t been done, doesn’t mean it can’t be done. So as a thought experiment, let’s explore the potential of eliminating low-quality hospitals to create a narrow-er network. For the sake of simplicity – and to avoid re-hashing the post on HPNs – let’s ignore issues like referral patterns, hospitals that perform well in one area and poorly in another, and the feasibility of excluding a single facility from a multi-hospital chain.

But before we go any further, we must define what we mean by “the worst-performing hospitals.” Even if we ignore uneven performance across hospital service lines, we still need to pick a composite measure of quality, and there’s no consensus on which composite measure, or source of measures, is the standing authority. NEJM Catalyst’s evaluation of Hospital Rating Systems can tell us that – at best – all the publicly available rating systems have serious flaws, and moreover, that the rating systems fail to create consensus on which hospitals are best and worst performing.

There are still more factors requiring careful consideration:

- Geography: If a low-performing hospital is the only hospital serving a community, carving it out of the network serves no one.

- Case Mix/Patient Utilization: If a low-quality hospital has low utilization from the current patient base, cutting it out of the network can send a message but will have a negligible impact on population health.

- Cost Impact: The lack of a correlation between hospital costs and quality has been well-documented. But a lack of correlation is different than an inverse correlation – i.e. removing the lowest-quality hospitals may not produce any cost of care savings – at least not in the short run.

The Covered California Health Exchange has one of the only published examples of a purchaser requiring its third-party administrators or contracted health plans to remove low-performing hospitals from their networks. Attachment 7 of Covered California’s Health Benefit Exchange Contract speaks to the State’s quality, network management and delivery system transformation provisions; the organization is currently in the process of updating these for Plan Years 2022-2025. The 2017 version specifies that health plans must either “exclude those Providers that are ‘outlier poor performers’ on either cost or quality from Covered California Provider networks” or justify the continuation of the contract.

The risk of exclusion from Covered California, which in 2019 enrolled 1.39 Million individuals, should make every hospital with poor outcomes nervous. However, although the threat is real, the foundational motive is “Less about narrowing the network, more about setting a deadline for quality improvement,” according to Lance Lang, Chief Medical Officer at Covered California. Attachment 7 stipulates that a health plan’s justification for keeping a low-performing hospital in its network must include “efforts that the provider is under-taking to improve performance” and that the health plan’s rationale can be made public by Covered California. Moreover, through funding from CMS’s Partnership for Patients program, Covered California has offered resources to help providers improve their performance.

Essentially, Covered California’s strategy is two-fold:

- Create a single set of quality metrics that all health plans must use to evaluate hospital performance

- Use the power of public reporting, along with the collective weight of Covered California health plans, to compel hospitals to engage – holding both health plans and providers accountable for performance improvement

Thus, the goal is conversation and collaboration, not expulsion. Moving forward, it appears that Covered California plans to continue building on this strategy. An August 2021 presentation from its Attachment 7 Refresh Workgroup Meeting and Webinar included the following goal: “To ensure high-value health plan networks through measuring the quality and cost performance of physician groups and hospitals; health plans should not only contract with higher performers, but also work to improve performance of lower performers.”

Are you considering evaluating a high-performance network program? Use CPR’s Reform Evaluation Framework to get started!

Julianne McGarry wrote this blog post in October 2019. CPR staff updated it in 2021. Photo by Rod Long on Unsplash.