Unpacking the complexity of high-performance network design

The National Business Group on Health (NBGH) predicted that by 2018 a staggering 61% of employers would offer narrow or high-performance networks (HPNs). The reality in 2019, according to the major consulting houses, is more in the range of 13 – 18%. NBGH wasn’t alone in its forecast of the rise of the HPN. Nearly all major benefit surveys reported the same anticipation – and employers continue to report that they’re considering an HPN as a means of reducing costs and improving quality. So, what accounts for the delay?

The problem may be supply. CPR’s interviews with 12 national and regional carriers found that none of them offered a multi-market network that consistently put quality first and generated cost of care savings.

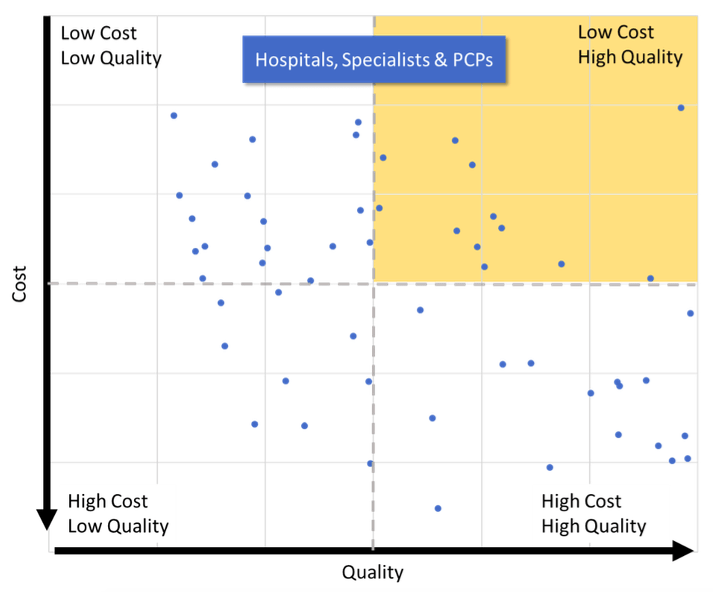

On its face, this seems surprising. If the employer demand is out there, shouldn’t it be relatively easy to build a national network of the highest-quality, most cost-effective doctors and hospitals? After all, every health plan collects quality, cost and utilization data, and the number of states supplying health care transparency data to the public continues to grow. CMS is poised to produce Medicare physician performance data through its Physician Compare Initiative, and thanks to the recently published RAND study on hospital prices, we know the unit costs of hospitals relative to Medicare in 25 states. It seems we’re set up to array providers on a 2 by 2 matrix of quality vs. cost, then grab the cream of the crop to forge an HPN around these elite performers.

You could call this a “net-casting” or “filtering” approach to network construction, and, while it seems simple, the reality is much more complicated.

Providers don’t operate like Legos, they’re more like strings of Christmas tree lights.

First of all, because we use different metrics to evaluate doctors vs. facilities, a net-catching approach runs the risk of networks where referral patterns don’t connect: e.g. none of the high-performing neurosurgeons have admitting privileges at any high-performing hospitals and vice versa.

There’s also the problem of consistency. Ignoring for a moment the performance variation among individual doctors in the same group practice, there is also significant variation among hospitals within the same health system. Moreover, it’s been well-documented that different hospitals excel at different specialties: the best hospital for rare cancers may perform terribly in maternity outcomes. But no hospital worth its negotiating salt will agree to be in network for maternity but out of network for neurosurgery; nor will a health system agree to contract with 3 of its satellite hospitals but exclude its flagship campus.

A “one-size fits all” approach overlooks variation in local health care dynamics

It’s news to no one that health care is local: the way people access health care, select providers, and use technology varies by region, by state and by market. Provider market dynamics also vary: by their degree of consolidation, their willingness to enter into value-oriented care contracts, and by the differences in quality and cost across and among provider groups. There are some markets dominated by a single hospital or health system: you can’t build an HPN in the absence of choice. A single set of quality and cost tests applied nationwide will either set the bar too high or too low in any particular market, and ignore opportunity to build strategic provider partnerships in response to each market’s specific needs.

Instead of looking for the right net, pursue “The A Team”

Here’s the good news: there are smart ways to build an HPN that produce greater efficiency, quality, and cost savings. While methods and specifics vary, the new thinking on HPN network design converges around the following two principles:

- Anchor your network around providers in value-oriented contracts (also known as value-based contracts or VBCs)

- Design your HPN for the market(s) you’re in

Let’s unpack these one at a time.

Anchor around value-based contracts

Your HPN creates incentives for patients to seek care from high-quality, low-cost providers. So, shouldn’t the providers in the HPN also have incentives to deliver high-quality, cost-effective care?

Also, let’s face it: an HPN by itself isn’t a strong performance incentive. Providers are promised additional volume, but that’s pretty weak sauce – especially for providers who have taken steeper discounts and fear that their existing business will be cannibalized by the HPN. A provider in a value-based contract, however, feels year over year pressure to achieve and sustain results; they lose the opportunity for shared savings – or worse – suffer financial penalties if their performance deteriorates. This does not mean that every provider in a value-based contract is a prime candidate for an HPN – far from it. Value-based contracts are a tool to influence provider behavior, not an inherent measurement of it, and there are plenty of low performing ACOs that wouldn’t make anyone’s A-team.

Anchoring an HPN around providers in value-based contracts does the following:

- Provides access to historical total cost and quality performance, enabling selection of providers with a “proven track record” of success

- Offers short and long-term financial incentives for sustained and evolving performance targets

- Creates the opportunity for deeper partnership opportunities, data sharing, and the introduction of new care models

Design your HPN for the Market(s) you’re in

Different markets demand different network strategies. In a market where providers are at a high risk of consolidation, purchasers and health plans have a vested interest in using their networks to protect independent hospitals and provider groups. In markets where providers are already highly consolidated, there may be opportunity to introduce sophisticated payment models with shared risk or global risk. And some markets where a single hospital/health system is the only option, purchasers will need to use creative tools like telemedicine and centers of excellence to create non-traditional networks. Ultimately, design flexibility is critical for exacting maximum value from the HPN, and ensuring the right tools and strategies are applied to the right market.

One last thought: Networks should be built to last

Health care is in a constant state of evolution. The standards of excellence we use today for quality, access and efficiency may be completely moot a few years from now. Imagine how we might evaluate care delivery partners in a world where the bricks and mortar hospital has become obsolete, where claims and clinical data integration are a standard requirement, where we evaluate patient experience for care delivered by AI.

Since care delivery models continue to evolve, you want an HPN built of provider partners who can evolve in tandem, and who are willing to embrace new and disruptive care delivery models. A network founded on relationships, trust, and deep understanding of the market ensures that the high-performing providers today continue to deliver excellence in the future.

While the net-casting approach to network design may look elegant within a 2×2 matrix, in reality, it creates a maze full of dead ends and blind cliffs that patients must navigate, and where making the wrong choice can lead to financial disaster. We hope that this background will also help employer-purchasers understand what to look for in a high-performance network, to forgive the complexity, and be suspicious of claims of value by algorithm. Just remember this: if you’re looking for a network that will deliver consistent high-performance, don’t look for a network designed like a fishing net, look for a one designed like a fantasy football team.